Russ Flatt and Kieran Scott – Two views on a landscape

The Landing is a site of bicultural exchange that was pivotal in New Zealand’s history. Two photographers – one Māori, one Pākehā – address the weight of that history in a unique art project.

Artists and photographers Russ Flatt (Ngāti Kahungungu) and Kieran Scott – one Māori, one Pākehā – visited The Landing together in mid-2020 for an art project that responded to the rich history of the place. Their very different responses to this brief led to a series of works that now occupy The Landing Suites in The Hotel Britomart. Here, Jeremy Hansen talks to them about the project and the photographs that came from it.

JEREMY HANSEN Russ, how would you describe what you do?

RUSS FLATT In my art practice I work around specific themes including identity, role play, sexuality and memory. The history of The Landing spoke to me about identity. The place of significant historical interactions between Māori and European intersecting on sacred lands.

JEREMY HANSEN How about you Kieran?

KIERAN SCOTT I’m still practicing. I’m a documentary photographer that bridges that gap between documenting and art making. I live in both worlds. I borrow stylistically from history, from printmaking, from watercolour, from other art forms that aren’t photography. I rely heavily on allowing moments just to reveal themselves. I’m not someone who orchestrates anything that I approach. I’m a Pākehā colonial photographer. My perspective is always trying to figure out my place in Aotearoa.

RF I think because of my background, my mother being Māori, my father being a British colonial, being bicultural, and travelling and living overseas for quite a number of years, I view Aotearoa in a different way. The project at The Landing was about looking at the land, looking at that history, and then treating the project in a visceral way - allowing the work to unfold and happen rather than forcing anything.

JEREMY HANSEN How did your research influence your approach to the project?

KS I did quite a bit of reading on the relationship between the local hapū and first contact with European sailors. The thing I didn’t know about was that Māori borrowed heavily from Pākehā and vice versa. It was quite a harmonious relationship at the beginning. I was very interested in trying to take that understanding and translate that by referencing the natural resources that were there – the flax and bullrush – and the nature of the landscape, looking at it from the colonial perspective of potential, and also the Māori perspective of it being sacred and important. Having an understanding of that relationship allowed me to unravel those relations a bit.

RF What surprised me through the reading was how Te Pahi welcomed Europeans into the bay, and how entrepreneurial he was in trade. What fascinated me more was how he travelled to Sydney to look further at how he could help his people, his iwi, his tribe. From a young age I had been brought up to believe that Europeans came in and basically took over; hearing that Te Pahi was very active in his ways of thinking and how he wanted to advance his people was really eye-opening for me.

JEREMY HANSEN Russ, you talked about letting the work unfold when you were shooting at The Landing? What was your process while you were shooting?

RF In the evening before I would go out I would say a karakia to acknowledge the past, present and future, and be still and let the wairua of the place wash over me. I tried to be led by instinct and something otherworldly, I guess. And that gave me the freedom to not feel that anything I did was right or wrong, I just let it be. My perspective was Māori on land, looking out to sea. It was very important not to show anything from the present day, like manicured lawns or modern fencing. I wanted it to feel like it was from the past.

KS It felt like you were looking through the fog of time, and the images needed to be like that. Russ worked almost in the dark and I worked in the light. Our paths never really crossed that much. I’d see you on a hill and you’d be finished and I’d be staring.

RF And I’d see you and think I should finish to give you your space to create. We come from a space where our artistic practices are so polar opposite. I worked at either end of the day and Kieran worked during daylight. Kieran approached it as a document he was creating to take back to show people.

KS I’m a documentary photographer primarily and I’m interested in relaying the facts. That’s a Pākehā perspective – gathering data, making maps, rather than accepting what’s around you.

RF And my practice is more about storytelling.

JEREMY HANSEN Did it feel like a project you were doing together?

RF Yeah, because we would come together in the evenings and talk about our day and make sure we weren’t doing the same things or sitting in the same places. Even though our perspectives were different, it was important we didn’t feel like we were following each other around.

KS Another interesting thing was that I chose to use a very analogue style using film that I couldn’t look at at the end of the day, and you chose digital.

RF I think because I wanted to experiment with technology and it was all about the light: long exposures and getting this mystical kind of ethereal imagery. And I wanted to know it was in the right place before I could kind of move on. Using film would have been too difficult for the process that I was using here.

KS It would have got in the way of your connectivity. I worked the other way around where I would make the pictures and come home and do little drawings and maps and think about what could come next. I was reviewing what I was doing but it was very analogue. I spent a lot of time looking at early photography, Victorian-era painting, notes by Joseph Banks and the colour of the paper, that slightly worn sepia. The primary work is done on film and then the post production is done digitally. I degraded them slightly, and pushed them to a place where they felt right.

JEREMY HANSEN You both seem to have resisted making work that was simply about the scenery – which must be tempting in such a beautiful place.

RF We had a lot of discussion about how we could avoid making stereotypical pictorial depictions of the scenes. For me it was the light, and steering away from any suggestions that anyone had been there. I like the idea of when you look at an image, the viewer has to work and really look to see what it really is. Somebody has to take the time and enjoy the process of trying to decipher it.

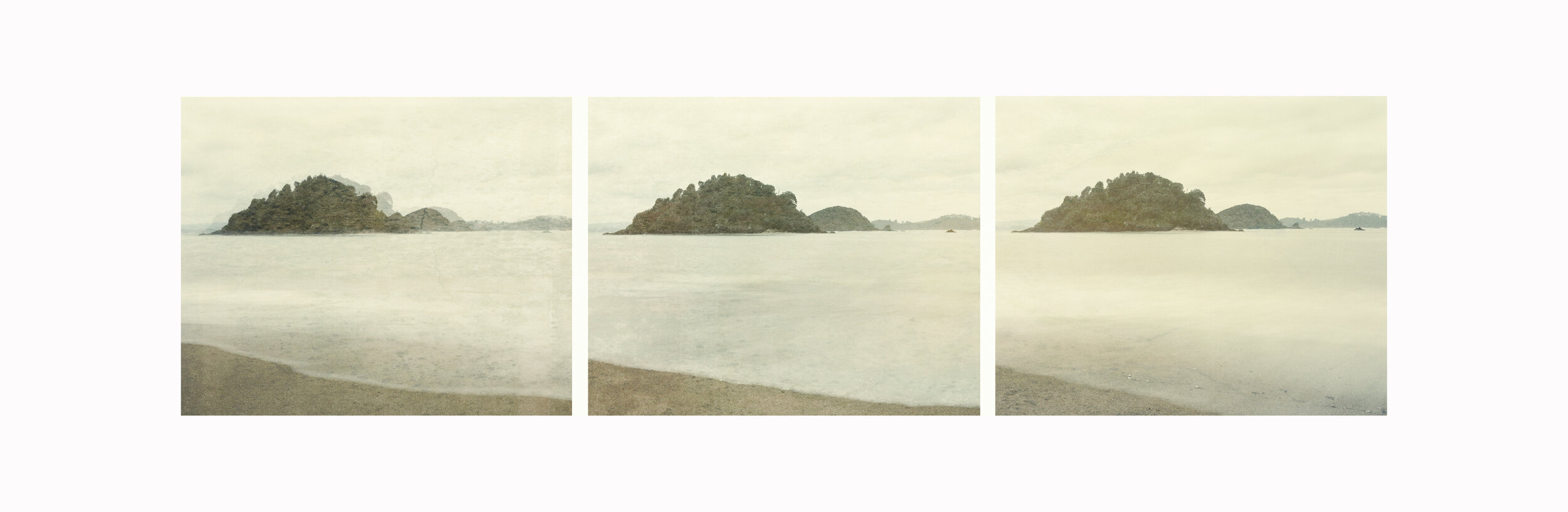

KS It’s about documenting and telling the truth about a landscape rather than trying to elicit some kind of emotive response to it. What you do then I think is you alter the viewers’ expectations. They look at the image expectiving the scenographic and they see the topographic. So instead of just thinking that’s beautiful, they investigate it more. When we were there the land presented this to us – it wasn’t prepared to give us blue skies and sunshine. It wasn’t ready to reveal itself to us. The other thing is that I’ve used triptychs and diptychs of the same thing, which is about time, and about movement and about immigration, the flow of people into and out from the shore.

JEREMY HANSEN The wave is a common motif in both your works.

RF it’s the sky that meets the water that meets the land. Those three things.

KS That’s all you have to work with really.